Warsaw-Tehran-Tel Aviv: more than I bargained for

- Ronnie Dunetz

- Jul 28, 2025

- 41 min read

Updated: Aug 2, 2025

I knew that this trip wasn’t going to be easy. Far from the usual preparation, excitement and planning for a trip abroad one I knew a priori that this trip to Poland was more of a “journey”, not one that gobbles up kilometers but one that reaches deep into the soul. While my true “roots trip” was and will continue to be a few hundred kilometers east of the Polish Belarus border- the town of Dzyatlava (“Zhetl”, the Yiddish name)- I was quite sure that “Poland” represented a much larger “Mecca” for my roots: the Yiddish language, huge centers of learning, Jewish history and civilization that lasted for nearly 1000 years. To visit Poland for the first time beckoned me to bring myself up the learning curve in an active way, seeking what I wished to learn and to do it with depth, feeling, a non-judgmental eye and an open mind.

Of course, visiting Poland for the first time meant that I was to engage with the Holocaust in a way that I had not as yet done. As a child of a Holocaust survivor father who had lost nearly his whole family just on the other side of the border, and as one who has since childhood been close to the subject both on a personal family level as well as a doctoral student writing a dissertation on the second-generation, I was not coming to Poland as a “Holocaust student novice”. Or so I thought. In reality, this would be the first time for me to engage with Holocaust memory on a huge scale. Poland has so many reminders and memorials, it would be the first time for me to be reminded that wherever I walked there were once Jews, most of whom who were eliminated from their home and lives by murder.

My months of preparation and study enabled me to know where it was I wanted to go, and to make contact with Poles today who volunteer to keep Jewish memory and sites alive. I was full of anticipation for these meetings.

In the end, I got more than I bargained for: two days into our trip I woke up early in the morning to read that Israeli planes had bombed more than a dozen Iranian military installations. Iran was quick to retaliate sending hundreds of missiles towards Israel, most but not all were intercepted. There were direct hits in Israel, 31 people were killed, hundreds wounded, thousands more were displaced from their homes which suffered extensive damage. Only two days into my long-awaited journey, my wife Merav and I found ourselves in Poland physically but emotionally back and forth with our children and baby grandchild waking up all through the night to rush into the “mamad” (secure rooms) because of sirens going off. While I hoped to have this time to dive deep into emotional history of importance to me, in essence life was telling me that history would need to make amends and take a back seat to present day ups and downs.

And so it was- at times I could feel and imagine how it was to be Jewish in Poland of the 16th century, but this was interrupted by 2025 Israel. The Holocaust ended in 1945, and I could readily feel into those horrific years of 1939-1945, the years of the greatest catastrophe in modern Jewish history- as well as the years of the greatest tragedy in my own family history. At times I was 80 years back, at others I was totally absorbed in the news from Israel being flashed on Polish TV or Israeli YNET internet. This was what I call “Warsaw-Tehran- Tel Aviv” and it went on for a full 12 days, much more than I bargained for but also an experience that heightened my sensitivity to all the emotions that can and do come up.

In this spirit I come to the words in this document, not fully aware yet of how this comes together- if it comes together at all. I am also aware of the paradoxes I raise, even the conflicting opinions and perspectives I myself will voice. This is the spirit and complex reality of these times, for me at least, and it is with this which I will write.

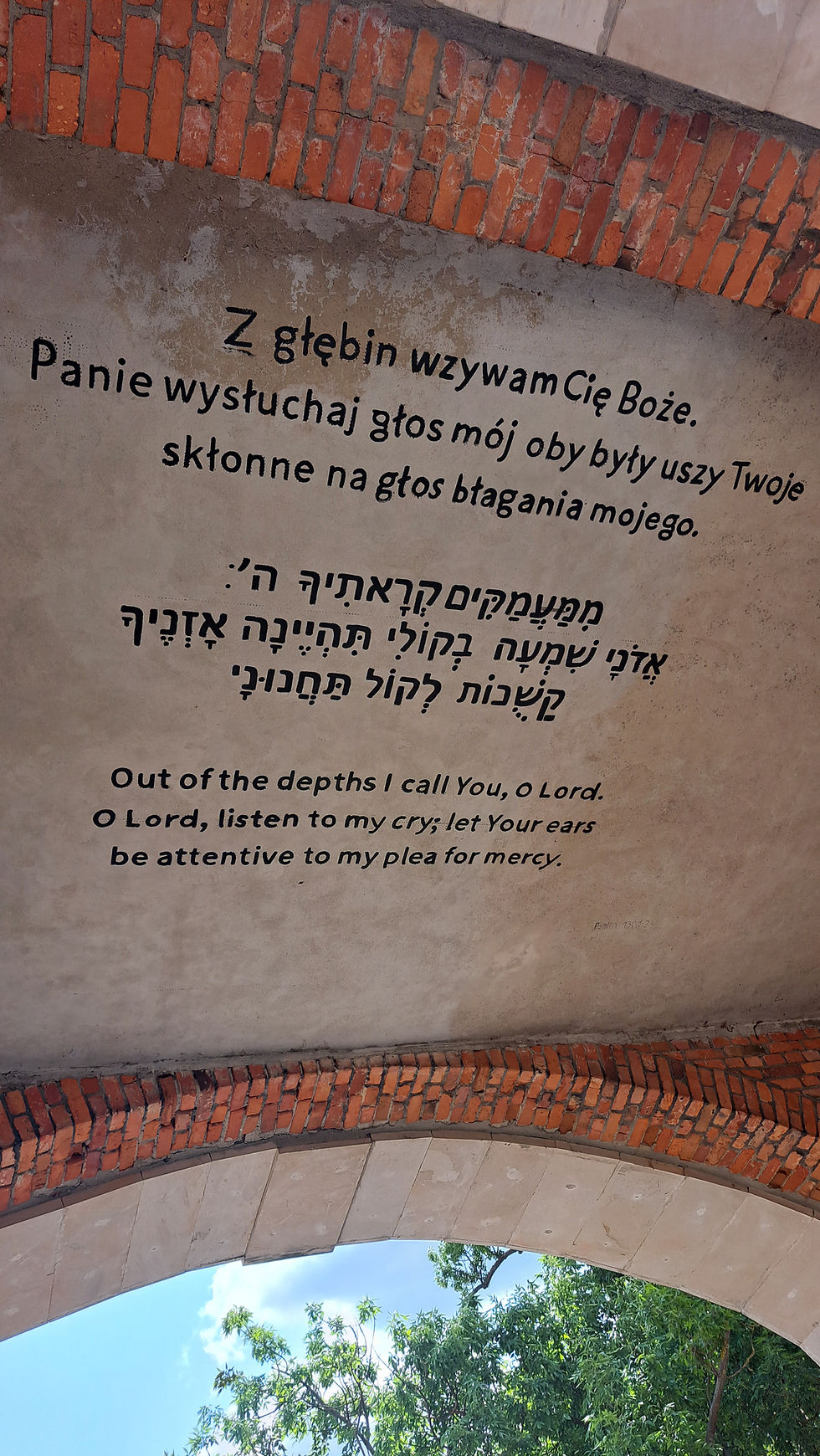

Under the "Grodzka Gate" in Lublin—once the link between the Jewish and Christian quarters.

Going to Poland? Why? I wouldn’t go there- just one huge Jewish cemetery

This is a response that you will still hear from many Israelis, Jews in general, even though there are thousands us who visit Poland yearly (the “March of the Living” alone brings in about 10,000 people yearly). I have a real dislike for this attitude, it is so limiting, so closed-minded, not allowing for life to go forward, for exploration to take place. I am embarrassed to say that this is exactly what I used to say not too long ago. There is something about “Poland” in the mindset of most of us that keeps us away, something in the mere name that brings up association with one thing and one thing only- Holocaust. I am not surprised that many people will travel easily and frequently to Germany, the heart of and home of the Nazis from 1933-1945(and many who lived on long after that), but Poland? God Forbid, Poland is Holocaust in their minds, Germany it seems at times are the “good guys”. Something is very warped here. Poland didn’t “do” the Holocaust, Germany did. Yes, I know all about the immense collaboration, will get to that later.

But, on the other hand… This statement is absolutely true! About 3 million Jews, half of all Holocaust murders, took place on the territory of what was Poland at the time. There has never been a bigger killing field of Jews than Polish territory. This fact will never be erased, no matter what narrative any given government or political party will try and promote. There were about 3.3 million Jews in 1939 in Poland, 300,000 remained alive, mostly those who managed to escape into the Soviet Union as the Nazis invaded. Jewish society in Poland was nearly wiped out, what remained moved under communist rule. Those who returned were appalled at the pogroms that sprung up in tens of places, the hatred they encountered. A mass exodus took place, communist rule of 44 years wiped out Jewish identity, those who remained lived out their lives often keeping their Jewishness a secret. There was no talking about the “Jewish plight” in the Holocaust, it was all “our Polish plight” under communist rule.

I quickly experienced Poland as “touring the absence”. I needed to use my historical knowledge and imagination to recall “what was”- we took a free walking tour of the Warsaw ghetto area ( 3.4 square kilometers in which the Nazis crammed in 500,000 people, many who died of starvation and disease). The walking “tour” was about seeing a bridge and a small part of a wall, hearing stories, seeing monuments and that’s about it. The city was totally destroyed in the war, but we were able to use the stories that we had grown up on and the input of the guide to “recreate”- more or less. That was my experience early on in Warsaw, we were walking in the land of the “absent, if you did not look for it you would not find too much. We walked and walked, used our brain and pain to get a feel of the horrendous reality that walked these streets some 80+ years ago.

On Friday evening, Shabbat eve, we went to the Nozyk synagogue, the only surviving prewar Jewish house of prayer in Warsaw. It is orthodox, is operational in that it also houses the various Jewish organizations in Warsaw. Before the war there were over 400 prayer houses in Warsaw. While I am very comfortable and “conversant” in the Friday evening prayers, I am not orthodox and only very infrequently attend services. This did not matter to me, I wanted to be there on this Friday evening in Warsaw, for me it had symbolic and sentimental value. As I walked into the synagogue, which was not full by any means, I saw Rabbi Michael Schudrich, the Chief Rabbi of Poland. Rabbi Schudrich- then only “Michael”- was a classmate of my brother growing up in New York. We had communicated over the years but this was the first time we had actually met. Rabbi Schudrich gave me a warm embrace and welcome. He is a man with many important accomplishments to his name, worthy of the title and the position he holds. I felt that this embrace on the Sabbat eve in the Warsaw synagogue was symbolic for the trip I had initiated which had just begun.

POLIN Museum: A Thousand Years of Jewish Life in Poland

Polin Museum: designed by a Finnish architect and Polish partner

I am not a big museum-go-er on the whole, I generally find them tiring, boring, overwhelming or just plain uninspiring. But my visit to “POLIN Museum” was just the opposite. This museum is really the first of its kind, built on the historic footprint of the Warsaw Ghetto—directly facing the Monument to the Ghetto Heroes. It’s more than a museum: it’s a living narrative of 1,000 years of Jewish life in Poland, from medieval arrival of Jews from the West to the catastrophe of the Holocaust, Communist time and postwar revival. I was deeply impressed by its unique architecture, effective use of multimedia, but most of all by the crowds of Polish students who were lined up to enter the museum.

This is a unique place which talks about Jewish civilization in Poland over the centuries and it is one that teaches today’s Poles, who most have likely never met a Jew, the size of the Jewish community only 86 years ago and haven’t a clue about the impact Jewish presence in their country before the war: 10% of the population, 30% in many of the many cities, over 50% in hundreds of small towns (“shtetls”) all throughout. This to me is very moving- to acknowledge Polish Jewish History with scholarly rigor, cultural activity, as well as a growing oral-history department among other things. Under Soviet rule, Jewish history was subsumed into a generalized narrative of Soviet heroism. POLIN’s founding marked a significant reassertion of Jewish cultural memory in post-communist Poland. I was invited to sit in front of a camera and tell the story of my father, which I did for 2.5 hours, which I will touch on later.

However, as impressive as it is, POLIN museum has not been able to stay clear of political confrontation. It took about 20 years to establish the museum, which is a public-private venture and that means that there were many hurdles to overcome. After 2015, nationalist politicians challenged POLIN’s leadership and censored exhibitions they felt criticized Polish history, which led to the dismissal of Director Dariusz Stola. In 2023, the Nationalist party was voted out and POLIN was given more authentic space, but very recently Poland elected an incoming president Karol Nawrocki, known as a right-wing Historian with a “Holocaust revisionist” orientation. Poland’s National Institute of Memory has consistently promoted a narrative emphasizing Polish suffering and heroism while downplaying wartime Polish complicity. POLIN apparently can only go so far in some areas in presenting history, it has been accused of painting and “over rosy” picture of Polish tolerance to Jews and undermining the antisemitism. I will address this below under “The Narrative” section.

And then the rockets fell

Two days into our trip, and the night following a deeply moving day at the POLIN Museum, life suddenly changed: Iranian rockets began to be launched en masse on Israeli towns and cities, many were intercepted, some got through. Citizens were killed, hundreds wounded, extensive damage to homes, thousands displaced from their homes. Waking up at 3:00 AM to check the YNET news was more of an instinct, and it continued from then on for our entire trip. Our children and infant grandchild were in and out of secured rooms during the nights and we were in Poland, far away. Here I was deeply engrossed and engaged with history of 800 or 80 years ago, in well-organized museums and comfortable hotels and restaurants, while back home fear, fatigue and insecurity abound. To say that we felt guilty being where we were is an understatement- not that we had anyway to get home, all flights were canceled for days. We were here and our loved ones were at home, nothing could be done about that.

I would be remiss if I did not mention a fleeting thought about how this was also somewhat symbolic: 80+ years ago the Nazis began to eliminate my people, my family, from the face of the earth where they were living only because they were Jews. They were helpless and caught in a trap they could not get out of. Today, an Iranian, fundamental Muslim regime 1500 kilometers away has threatened, and attempted to eliminate the Jewish state for years. Only today, this state created for the Jewish people has the power, ability and initiative to protect itself. I don’t want to belabor this point, it is a different world, a different time and a different status- but still symbolism does not need all those things to be penetrating.

Eastward for the Sake of Memory: Searching for Roots in Białystok

Tomasz Wiśniewski has documented Jewish cemeteries of Bialystok and has extensive expertise. He has created “Miejsce” — The Place- a small museum dedicated to the history of Jews in Bialystok.

Without Tomasz I would not have found it, amongst the bushes. The grave of Rabbi Yisrael Dunietz, died 1927.

I have always assumed that my family roots through my father’s family in what is today Belarus, were primarily in Zhetl. However, in 2014 when I did some family history work I came upon a brother of my eccentric but remarkable great grandfather Shlomo Zalman Duneitz, Rabbi Israel Dunietz, who lived and died in the Eastern Polish city of Bialystok. I learned that there were more distant relatives in the greater Bialystok area, which excited me. In fact, due to the dedicated work of one truly amazing “activist” of Jewish memory for more than 3 decades, the journalist, cultural expert and creator small Jewish museum in the city called “The Place” or “Miejsce”, Tomasz Wisniewski, I learned that Israel Dunietz’s grave could be located. Tomasz took us to the cemetery, and after 30 minutes of searching and cutting through bushes, we came upon this grave. I wondered to myself if anyone ever visited this grave from our family since the Holocaust. Rabbi Israel Dunietz died in 1927. I felt that I had been able to create a tiny bit of history that will never be recorded.

It is important to understand that the majority of Jewish cemeteries in Poland, and nearly all of Eastern Europe, are poorly maintained, if at all. Some larger cities have some level of care by volunteers but abandoned or destroyed cemeteries are widespread and the rule in small towns. Many were desecrated during WWII or in the communist era—gravestones were used for construction, roads, or left to decay. Restoration efforts have increased in recent decades. Still, hundreds remain overgrown, vandalized, or even unmarked. This is one of the ongoing reminders of just how the memory of the Holocaust continues to have physical manifestations.

When we came upon the grave of Israel Dunietz I felt a surge of emotion overcome me and I wondered why this was so- he was a distant relative and one that I had never heard of until some 10 years ago. But this did not matter, because for the first time in my life I had an actual grave to visit from the entire history of the Dunetz family in Poland/Belarus. Hundreds of relatives that came before me lived and died there and not one grave was in existence- until this “discovery”. It was a personal tombstone of a relative who died a normal death, at an older age; not the emptiness and sadness of a mass grave of Jews, my family included, who were violently murdered during their lifetime.

Bialystok used to be a major Jewish city in Northeast Poland, today there are said to be about 20 Jews, none with family roots in the city. Yet, the Jewish past can be found in various places around the city. One place we happened to pass by which was especially moving was the Cytron synagogue dating from 1936-1937 and reconstructed in the 1970s. It was the only synagogue that operated (illegally) during the ghetto times of the Holocaust, before liquidation of the town’s 50,000 Jews. During reconstruction in the 1970’s they found many Jewish religious items- some of them were handed into the city museum and others were stored in the attic. Recently, some 50 years later, people by chance came upon pre-war boxes in the attic from before the war. They found old prayer books, torah scrolls, prayer shawl, among others. Today these items are under display for those interested.

Meeting the Memory Keepers: Conversations with Polish Activists

One of things that most intrigued me on this journey was to meet and get to know people who are known by a overly-general term “Polish activists for Jewish memory”. These “activists” come totally on a volunteer basis, they are all over Poland and seem to often be working on their own, although there are organizational connections. Ever since “discovering” that there even was such a phenomenon over the past few years I have been curious to meet them face-to-face and ask them- “What brings you to this work?” To be honest, regarding this aspect of my journey I feel somewhat disappointed that I did not manage to meet enough of these admirable human beings, and to meet them in a “deeper conversation”. While I did have some very memorable meetings that I will describe below, perhaps I did not meet enough of the “right people”, or come through the “right introductions”. Much of my communication prior to the journey was never answered. Perhaps it is just a first stage and more will come. We shall see up ahead.

Meeting Mariusz Sokołowski and his family at his home in suburban Bialystok left me moved and inspired. A pleasant man in his 40’s, Mariusz has been in this space of “Jewish memory” ever since his university days, taking part in co-creating the Jewish Heritage Trail in Białystok and participated in the Jewish cemeteries in Krynki and Michałowo. Later, as a teacher, and now a principal of a school, he has engaged students in learning about the local, multicultural history of Bialystok through various creative means.

I asked Mariusz if is focus on the heritage of Jews, who no longer live in Bialystok, is something that is widely accepted without resistance. What I understood was that not everybody sees eye to eye with it (including friends from the past), but that most colleagues, students, friends and neighbours appreciate, cooperate and value his initiatives.

Mariusz Sokołowski and wife: an educator who has been involved with Jewish memory projects for about half his life

During communism discussing the Jewish past, the Holocaust or anything uniquely Jewish, was often politically suppressed and could be personally dangerous. The efforts to preserve Jewish memory in Poland began in small, often isolated forms in the late 1970s and 1980s, under communism, and grew significantly in the 1990s and beyond after the fall of communism. This activity is by no means “mainstream Poland”, much of the funding has come from Jewish organizations abroad, EU, embassies, etc. It is still “off the beaten track” but recognition is growing, especially among the younger generations, which is very encouraging. Hundreds of towns and villages now have some local project or initiative, more than 40 “Jewish culture festivals” take place annually across Poland. There have been hundreds of grassroots efforts all over Poland- often involving high school children: volunteers, teachers, historians, artists, and young activists began preserving cemeteries, cleaning up sites, and organizing local events. The Forum for Dialog is one organization that unites these activists.

What, then, is their motivation to do such voluntary work? Many feel a deep sense of moral obligation to honor the erased Jewish past of their towns; for decades, postwar Poland often remained silent about its Jewish population. Activists are now confronting this silence. Some see this work as a form of Polish-Jewish reconciliation, many of the new activists are young Poles who grew up without Jewish neighbors and are driven by curiosity, conscience, and a thirst for truth. Many activists collaborate with descendants of Jews who lived in their towns before the war.

Lest we paint too rosy a picture, my sense is that most Poles are rather far and indifferent to this “activist work” and some are indeed critical and in opposition, mostly from the rightwing side of the political map. This group pushes back against this trend, accusing these efforts as “shaming Poland”, creating lies about “what really happened” during WWII, and can often voice antisemitic comments and rhetoric.

The people I did meet with, all of whom impressed me deeply, included

Tomek Pietrasiewicz , the Founder and Director of the Brama Grodzka–Teatr NN Centre. He is the recipient of numerous national and international awards for his pioneering work on Jewish memory in Lublin, where he has lived nearly his entire life. Brama Grodzka–Teatr NN Centre is a local government cultural institution that works towards the preservation of cultural heritage and education, with an emphasis on Jewish heritage of Lublin. Before the outbreak of World War II, there were approximately 43,000 Jews living in Lublin, Poland, comprising about one-third of the city's total population.

Tomek’s story and presence captivated me from the start when I first began researching the topic of “preservation of Jewish memory in Poland” online. By profession he is an actor and theatre director, at university he studied physics and in the past he was an opposition activist during the communist period in Poland. Tomek has said: “I felt there was something deeply not right about this situation – that an adult man living in this city doesn’t know anything about the Jews.” When I met Tomek in person in Lublin I was taken by his warmth, genuine disposition, simplicity and deep listening. Unfortunately, our conversation was through an interpreter in that Tomek apparently did not feel confident enough in his English. Inspired by what I had seen at Brama Grodzka, I very much looked forward to sharing some of my feelings, thoughts and ideas with Tomek for potential collaboration; however, the conversation that ran through the interpreter did not seem to carry this impact through. I regret that and hope to reconnect with Tomek- there is so much more to be said and done.

Unfortunately, our meeting with Marek, who is also the mayor of the small town of Orla not far from the Belarussian border, was very brief and limited to conversation over “google translate”. Marek is a warm and impressive man, whose family has been living in this small town- which once had a Jewish majority, and where Jews lived since the 16th century. The synagogue in Orla is a striking museum which Mark takes care of personally. We marveled at the renovation, were moved by the ambience in he far-east countryside and of course were saddened at the fate of the Orla Jews- as was the same everywhere. Marek impressed me by saying that it is very important to him that the synagogue be used only for appropriate events of culture and art. He firmly opposes the idea of having another “all-purpose room community parties and events”, this is not his not a respectable way of honoring the Jewish heritage that is close to his heart.

To round out this section, I would like to mention Dr. Artur Szyndler, the manager of the Oswiecim Jewish Museum. Oswiecim sounds like Auschwitz, not by chance, it is the historic town two kilometres from the infamous concentration and death camp of Auscwitz-Birkenau. Before the Holocaust, Oswiecim was just another Polish town with a 60% Jewish population and a vibrant community. Artur, who is not Jewish, spoke to us in between receiving tour groups who were awaiting entrance outside. I was taken by how this museum commemorates life of a community where 98% of its Jews were exterminated, many of them virtually down the road at the world’s greatest killing site of all time.

Facing the Narrative: Polish Collaboration in the Holocaust and the Shadows That Remain

One of the issues that preoccupied me for months before our journey to Poland was really getting my head around deeply understanding one question: if and to what extent were Poles collaborators in the murder of Jews in the Holocaust? Interestingly enough, I did not have the opportunity of engaging in any meaningful discussion around this on my trip, and I think that the main reason for this is that it is simply a topic nobody wants to be heard talking about too much. A taboo of sorts, or is just fear or discomfort?

I have my own stories to contribute on this one. My father told me a number of times that when he was in Lodz, Poland, for a number of weeks after the war in transit from Zhetl to the displaced persons camp in Germany, he was almost killed by two young Polish men while riding a train. He found himself alone in a train car one night with these two men and he overheard them talking about throwing my father off the train. Luckily, he was able to move to another carriage and get off the train before anything happened. My aunt Fanya, who survived with my father, also spoke of experiencing antisemitic encounters after the war.

The Polish narrative on collaboration with the Nazis during the Shoah has undergone a dramatic and painful evolution, marked by denial, shock, debate, and, in recent years, intensified political tension. For decades after World War II, the dominant Polish narrative emphasized the country’s suffering under Nazi occupation. Poles were portrayed as victims and heroes — resisting both Nazi and Soviet forces, with stories of righteous rescuers like Irena Sendler and the Żegota underground organization at the forefront. This view left little room for acknowledging Polish involvement in the persecution or murder of Jews. The Holocaust was remembered as something “done to Jews by Germans,” while the complex and often tragic role of many non-Jewish Poles was left unexamined.

This began to change in the early 2000s with the publication of Jan Tomasz Gross’s book Neighbors, which exposed how Polish villagers in Jedwabne murdered hundreds of their Jewish neighbors in 1941 — not under German orders, but on their own initiative. The revelation ignited a national scandal. For the first time, Poland was forced to confront a documented case of grassroots Polish violence against Jews during the Holocaust. The reaction was divided: some praised the courage to face historical truth and called for moral reckoning, while others accused Gross of slandering Poland and damaging its international reputation. The debate that followed — including state apologies, media discussions, academic inquiries, and local resistance — marked a profound rupture in how Poland engaged with its wartime past.

Jan Grabowski: a historian with courage and dedication to research on narratives in Poland regarding the plight of Jews

As more research followed — especially by scholars like Jan Grabowski and Barbara Engelking — additional evidence surfaced showing that collaboration, betrayal, and post-war violence against Jews were more widespread than previously admitted. According to Engelking and Grabowski: “Sizable parts of Polish populations participated in liquidation actions and later, during the period between 1942 and 1945, contributed directly or indirectly to the death of thousands of Jews who were seeking refuge among them.” These findings coincided with a growing nationalist resurgence in Poland. In 2018, the government passed a controversial amendment to the “Institute of National Remembrance” law, criminalizing public statements that suggest Poland or the Polish nation bore responsibility for Nazi crimes. The move was internationally condemned, particularly by Israel and Jewish organizations, and though parts of the law were softened, it sent a chilling message to historians and educators.

Today, the scandal has become part of a larger cultural and political battle over Poland’s identity and historical memory. On one side stand historians, memory activists, and educators who seek to confront difficult truths, often supported by international institutions. On the other are political leaders and nationalist voices who emphasize Polish heroism and martyrdom, resist what they call a “pedagogy of shame,” and view critical history as a threat to national honor. The issue remains deeply divisive, with lawsuits against historians, state-sponsored campaigns defending Poland’s image, and growing censorship in educational contexts. Nevertheless, public engagement with Holocaust memory continues through grassroots initiatives, youth education programs, and Jewish heritage preservation — a testament to the ongoing struggle over how Poland remembers and tells its past.

The victory of Karol Nawrocki, backed by the right-wing Law and Justice party (PiS), in the presidential election in early June, 2025, is likely to take bring this confrontation back into the front pages. Previously Nawrocki headed the Institute of National Remembrance- precisely the place that promotes the “defending the image of Poland”.

There are plenty of hurdles to deal with for someone hoping to understand what exactly was the situation in Poland. There was definitely a policy of punishment- even death- for Poles who helped Jews, thereby exploiting Polish fear. The Germans and Polish police sometimes killed Poles who hid Jews, which in turn led other Poles to preemptively murder Jews they were concealing—either with their own hands or by surrendering them. There is no doubt today that in a very definitive way, many Poles were not “mere bystanders” but were actively involved at one level or another of enabling the efforts of the Germans to annihilate Jews.

Similarly, there is a deliberate policy in Poland, as elsewhere in Europe, to play up the role of non-Jews in rescuing Jews. According to Grabowski few Poles were willing to help Jews, and those who were endured threats and sometimes retaliation, including murder, from fellow Poles. Nevertheless there were “righteous gentiles”- symbol of humanity shining amidst the greatest dangers of evil- were they informed upon and caught there was a death sentence for them and their families. According to the Yad Vashem: “Righteous Among the Nations are non-Jews who took great risks to save Jews during the Holocaust out of humanitarian motives. These were individuals who chose to stand against the prevailing evil and to help fellow human beings at a time when doing so meant danger to themselves, their families, and others.” Can anyone honestly say in their heart’s heart say they would have acted as a “righteous gentile” in such horrendous and dangerous times?

As of today, Yad Vashem has formally recognized 28,217 individuals from over 50 countries as Righteous Among the Nations. Among those remarkable individuals, 7,232 are Polish—making Poland the country with the highest number of Righteous recognized. This is no doubt worthy of the highest praise and admiration.

Yet, Prof. Jan Grabowski acknowledges this, but having researched this very troublesome area of Holocaust history emphasizes that tens if not hundreds of thousands of Poles were involved in acts against Jews during the Holocaust—through denunciation, betrayal, participation in murder, and helping the Nazis track Jews in hiding. Although exact numbers are hard to come by, Grabowski estimates that over 200,000 Jews who tried to hide in Poland were betrayed, discovered, or killed, with the help or direct involvement of local non-Jewish Poles. He writes:“Without the active participation of the local population, the Germans would not have been able to identify, hunt down, and murder so many Jews.” He argues that the Nazi “hunt for the Jews” succeeded not just because of German power, but because of widespread denunciations, blackmail, and collaboration by ordinary Poles. This includes village mayors, local police, neighbors, and civilians who denounced Jews in hiding or turned in those who helped them.

It goes without saying that Grabowski and Gross’s work have been highly controversial in Poland- they have faced lawsuits, public criticism, and even death threats for challenging the dominant national narrative of Polish innocence or heroism. While so much has and is happening in Poland, truth-telling about this aspect of the Holocaust in Poland is still work in progress, unfortunately. I wonder how many Poles today are willing to acknowledge the fact that the Polish people were definitely victims in World War II, however a great many of them were also perpetrators against Jews.

Kielce: The Pogrom, the Wound, and the Ongoing Reckoning

Yitzhak Shamir, the former Prime Minister of Israel, said in May 1989: ‘My father, Shlomo Ysernitzky, was killed after escaping from the train to the death map, while seeking shelter among friends in the village where he grew up. His [Polish] friends from childhood, killed him….the "Poles imbibe anti-Semitism with their mother's milk".” The comment made by Shamir was widely reported. Shamir’s mother and two sisters were also killed in the Holocaust. In 2019, the then Foreign Minister of Israel (today Defense Minister), Israel Katz, caused a national scandal with Poland as he too quoted Shamir’s statement and said: “"I am the son of Holocaust survivors, the memory of the Holocaust is not something to compromise about. It is obvious. We will not forget, and we will not forgive. Poles collaborated with the Nazis, definitely. You can't sugarcoat this history," he said.

We visited a small but memorable museum in the city of Kielce on our way to Krakow. I knew the story, my father’s friend, Raphael Blumenfeld, was a survivor of the Kielce Pogrom. The Kielce pogrom, which occurred on July 4, 1946, was a brutal anti-Jewish riot in the Polish city of Kielce, where 42 Holocaust survivors were murdered and over 40 wounded by a mob that included Polish civilians, soldiers, and police. Sparked by a false rumor of Jewish ritual kidnapping—a blood libel—it became a terrifying symbol of persistent antisemitism in postwar Poland, even after the horrors of the Holocaust. The pogrom shocked the world and devastated the hopes of many Jewish survivors who had returned home seeking to rebuild their lives. Its impact was profound: it led to a mass exodus of Jews from Poland, with tens of thousands choosing to emigrate, realizing that they had no future in their native country. The Kielce pogrom remains a stark reminder that antisemitism did not end with the defeat of Nazi Germany and continues to provoke debate about memory, guilt, and responsibility in postwar Europe.

Through the museum in Kielce I learned about the work and film of Bogdan Białek, a Polish Catholic psychoogist who, for over two decades, has courageously led public efforts to confront the truth about the Kielce Pogrom of 1946 — one of the worst post-Holocaust acts of antisemitic violence in Europe. At a time when most locals preferred silence or denial, Białek initiated open dialogue, commemorations, and Jewish-Christian reconciliation work in Kielce, his hometown. His film Bogdan’s Journey, which I viewed after my return home, touched me deeply. It chronicles Białek’s 20-year mission to bring the memory of the Kielce pogrom into the public conscience of Poland and create healing through truth-telling and interfaith dialogue.

Driving the S-19: A Journey Through Memory and Landscape

Sometimes I have these ideas which “look good” but when it comes to the actual implementation life throws a few curveballs at me. I thought it would be a very meaningful thing to do in driving down the S-19 highway in the far eastern part of Poland. This “borderlands” region near the Belarus and Ukrainian borders of today was once fully populated by tens if not hundreds of Jewish Shtetls. I thought it would be exciting to drive through some and stop every so often, so I read up and printed out some material-I did what is called “The Shtetl Route”, sticking to the Polish side of the border.

Perhaps a nice plan but in fact it turned into more of an ordeal! First off, the GPS in that part of the country is very erratic, which had us driving back and forth on the small picturesque roads, many of which are under construction. Nothing like driving 10 kilometers in the wrong direction and then tracking back and doing 10 in the other direction. This happened a number of times! I learned, once again, that I really dislike this kind of driving, so experiencing the beautiful green fields around competed with the ache in my upper back and the fatigue to my eyes. So much for romantic driving ideas- I am more convinced than ever that I prefer to walk 25 kilometers than drive 250.…still, what we did manage to see stirred up in me emotions- the town of Kock (pronounced kotsk), reminded me of the stories of the Rebbe of Kotsk, and there were other prominent shtetls I had learnt about. As we drove I kept imagining what it must have been like to be a Jew in this area 100 years ago, more or less living in a “Jewish enclave” in a small town but interacting with the “outside Gentile world” on market days and “official government matters”. The “Shtetl Route” enabled an extended visit to some gems in Eastern Poland: the city of Lublin and Kazimierz Dolny, located on the eastern bank of the Vistula (Wisła). Both, in their own right, have a beauty of their own and have significant, long-lost Jewish history. Here too it is the “absence” that is felt amidst it all.

Visit to Auschwitz: Walking Through a Memory of Horror

Can you recall those places, people and events that you always thought were “really important and critical” but, in the end, actually proved more disappointing that anything else? I am quite sure you have…so, here is one of mine: our visit to Auschwitz. I need to add that there are two reasons for this- one has nothing at all to do with Auschwitz itself and all that it represents, and the second has everything to do with it.

The first part, which has no residual value for the reader I will keep very short. I am including it only because these things happen on journeys around the world and it is all “part of the story”.

I messed up. It is as simple as that. These days you cannot just arrive at Auschwitz, come in and start walking around. If you do not come with your own group or guide you need to sign up and pay for one of their many group tours of 2.5 hours, in one of a multitude of languages. And you need to sign up well in advance to “gain a seat”, which I did, in English (although my wife’s native language is Hebrew, there is no group tour in Hebrew at present). Fair enough. Only for some reason I have yet to understand, I was remiss in not reading all the emails that came in explaining where to start the tour and park the car…so our google maps navigated us to the wrong parking spot and entrance- the Auschwitz site of today’s museum is actual “Auschwitz-Birkenau”, with Birkenau being 3 kilometers away.

As a result, we arrived late for our 11:00 tour, but not late enough to invalidate our booking. The museum staff appointed a young lady to give us head phones and march us into the camp area, chasing “our group”, whisking us by the different barracks on the side- we were “catching up”. When we were all caught after about 15 minutes, we arrived at our destination with about 30 others from all different countries, with the guide speaking a mile a minute in heavily Polish- accented English that I struggled to understand and my wife, Merav, completely shut down from not managing to follow. We raced on. In the end I lost my reading glasses when we needed to give back the headphones and board a shuttle for Birkenau(later retrieved). At the end of it all, tired and frustrated, we couldn’t find out how to get out of the parking lot as it was all automatic and the machine wasn’t scanning my card. I was asked to back out and let others in the line move ahead, which I did, and began looking for some employee to help me navigate the hurdle, which took me 30 minutes to do as they are cutting back on staff in favor of “technology”. Merav and I began to explode at each other until the machine allowed our car to pass…now isn’t all this totally ridiculous!? For this you go visit Auschwitz, one of the most “meaningful moments” in visiting Poland?

Of course, all this is really nonsense, totally insignificant in the end but very “significant” in accentuating any “tough moments” one encounters on any given journey. I guess it is all just “part of the journey”…And now what is really important…

Auschwitz-Birkenau: A Landscape That Defies the Imagination

Auschwitz is a place, concept and reality that defies imagination! It is estimated that over 1.1 million people were killed over a period of a few years, 90% of them Jews. About 90% of all those who were killed were murdered within a few hours of their arrival. They were sent directly from the train platform (called the "Judenrampe" or later, the Birkenau ramp) to the gas chambers, after a selection process by SS doctors. Auschwitz had 44 known subcamps for forced labor (satellite camps), which were often brutal, with starvation, beatings, disease, and executions common. No matter how hard you try it is impossible to get your mind around what kind of “death planet” this was.

And today, 80 years later, are some more numbers. Auschwitz is a kind of strange “memorial museum” that covers roughly:195 hectares = 480+ acres, about 365 football fields in size. Some parts are intact as they were back at the end of the war, others are restored for preservation. About 2 million people visit Auschwitz every year. It is estimated than less than 10% are Jewish. I find myself wondering: 2 million people each year, the great majority who are not Jewish, visit an unprecedented “scientifically-design” killing site which about 1.1 million people, the great majority of whom were Jewish. In essence, while every person who was exterminated in this hell is a world and a tragedy unto his/her own, and nobody has a “monopoly on suffering”, but isn’t this, by numbers alone, the most, sacred “Jewish site” in the history of the world? Is that the message that these visitors get? Is that the message that is promoted on the website the message that one sees when walking the cursed ground? I have some serious doubts. Auschwitz has been “globalized” and “internationalized”, something tells me that it is “better for tourism that way. I find myself at loss of words...

But there is something else that I feel no loss of words about- how utterly profane it is to see throngs of people on “Auschwitz tours”, walking from “museum site” to museum site, as if this were the Louvre, some national history museum or circus site! I understand the need people have for “dark tourism”, but there is something so utterly blasphemous to treat Auschwitz as an “attraction” and that is exactly what it is today: we move from the torture sites, to the rollcall sites, to the gas chambers, crematorium area, and of course, the windows to view the masses of shoes, hairbrushes, suitcases, among others. I shuddered at the thought of the 1.1 million screams of souls that left this world on these grounds, as well as the thousands of others who escaped them, barely...One of the most unsettling memories I have of Auschwitz is the chit-chat that a number of European teenagers or college students were having amongst themselves as we walked from “museum room to museum room”. The guide chided them that their voices were disturbing to those of us who want to “listen to him”. Can you chide them for more than that? Is this not just human nature, can we ever really “remember” such unfathomable atrocities? The guide very professionally moved us from site to site, other groups were behind us, many were before us. I felt moved, overwhelmed, helpless, angry and confused- all at the same time. This was Auschwitz for me at this time.

Majdanek Was Different: The Echoes of a Lesser-Spoken Camp

In contrast to my “Visiting Auschwitz experience”, our trip to the Majdanek death camp was something that felt memorable, meaningful and “sacred”. It was here that I had the feeling that I was not a “tourist” but a human being, a Jew, a relative, who had come on a type of pilgrimage to honor family members whose lives were brutally ended in the monstrosity of the Nazi hell on earth.

This does not mean that the soul is not battered from the moment of approach. Driving into the open air “Majdanek Museum” (the former camp grounds), the first thing you notice is how this horrific place is basically a suburb of the city of Lublin. Polish families were living their daily lives for years where just around the corner while…What makes Majdanek even more mind-boggling is that it all seems so “intact”- Unlike Auschwitz-Birkenau and the other Nazi death camps in Poland where much was destroyed by the fleeing Nazis, Majdanek was liberated quickly by the Soviet Army in July 1944, giving the Nazis little time to dismantle or cover up evidence. As a result Majdanek is the best-preserved Nazi extermination camp in its original location. You can “see it all”:

Zyklon B cannisters for gas chamber

Gas chamber

Crematorium

Original gas chamber: Still standing and accessible to visitors. It is one of the only preserved Nazi gas chambers at an original site.

Crematorium: Reconstructed after WWII on the original site using recovered materials. Some of it is original.

Barracks: Around 15 of the original wooden prisoner barracks are preserved, including storage buildings for shoes and personal belongings of victims.

Watchtowers and fences: Several original towers and fence sections remain.

Guardhouses and administrative buildings: Partially preserved.

Mass graves and remains: Ashes and human remains from cremations are interred in a massive mausoleum, built in 1969, near the crematorium. There is renovation and maintenance work going on at this time so we were not able to approach the mauseoleum. It didn’t really matter- one gets the idea very quickly and for 2.5 hours you walk around and “breathe it all in”- the rubber of what you know means the “road” of what you are seeing. Between 80,000 to 130,000 people were murdered in Majdanek.

It is here more than anywhere else in Poland that I felt my father’s presence. My father survived the Holocaust in another place, in Zhetl, Belarus (then occupied Poland), about 300 kilometers over the eastern border, but here died a family that was very dear to heart of my father: his aunt Miniote, her husband Avraham, and their three children- Raizele, Issac and Srulik (Israel), from the city of Volkovysk. My father was especially fond of them as he lived with them in his teenage years attending the Hebrew Gymnasium, which was very central to his life and identity. His aunt’s family was totally annhilated. For some “administrative” reason in the Nazi killing machine, Miniote’s family was deported to the Bialystok ghetto and then transported to death at Majdanek. I know little more than this, only that my father always had tears in his eyes when I asked him about this family. I never managed to talk to him too much about them, I regret that, as well as having the feeling that since this family was not living anymore in Zhetl, where our focus had always been, it was somehow removed from memory and commemoration. In fact, my father never did visit Volkovysk again, nor did I on my short Belarus pilgrimage. Perhaps this is something I can correct in the years ahead.

I came to Majdanek for my father as well. Although I believe some of our family’s “next generation”, the grandchildren, were at Majdanek for a short time on their high school “Poland trip”, I am quite sure that they did not come “prepared” for it as I did now. I had worked with a wonderful person I met through Servas in Poland, Ivonna Nowicka, who volunteered to do a virtual memory for Miniote's family. I came clutching the photos, the only photos my father had of this family and keep in “the album from then”. I said Kaddish and stood in silence, with their photos in my hand, thinking of my father and the memories he had which I never knew about. If photographs can speak, and if places keep their memory, I believe I was able to transmit something to these tragic members of my family whom I never knew. What I can say about Majdanek, I can say about all of Poland. The past lives in us just as the world moves on.

Kraków’s Jewish Cultural Festival: Admiration, Optimism—and Uneasy Questions

Krakow is a beautiful city. It has a well-preserved Old Town, lively squares, and rich cultural life. It offers a unique combination of medieval architecture, royal history, and Jewish heritage, all within walking distance. Unlike many cities in Poland, Krakow was not destroyed during World War II, which adds to its authentic charm. Its appeal lies in the balance between old-world atmosphere and a vibrant, modern cultural scene. We planned on staying only three nights in Krakow but stayed a full week due to flight cancelations. It is a good city to be “stranded in”.

What interested me most at this time, however, was not “Krakow the city” but Krakow’s Jewish Quarter (names “Kazimierz”) and its Jewish history and all that was going on at the time- the 34th annual Jewish Culture Festival. I was pulled like a magnet to show up at this festival daily, for hours at different sites around the city, often having to argue with my wife Merav with whom I agreed before we went to Poland that it would be about “half and half” during our trip: half Holocaust/Jewish stuff and have “regular traveling”. We more or less kept to it until we arrived in Krakow, with the extra three days due to our flight being canceled and this festival going on, I basically “lost it”. The magnet was pulling too strong.

A Jewish Culture Festival of 5 days in Poland? I wondered about that. Nobody knows how many Jews are in Poland, official estimates range in the 15,000-20,000, but some sources say there may be as many as 100,000 who claim some type of Jewish heritage, it is all very complicated and it definitely does not comply with the traditional “Halacha” (Jewish law) view of “Who is a Jew”. In Poland 80 years after the Holocaust, including over 40 years of communism, the rupture with the past is enormous. Rabbi Avi Baumol, an Israeli-American Rabbi who presided over the tiny Jewish community in Krakow for 11 years till 2024, often spoke and wrote about a powerful and recurring phenomenon during his years in Kraków: individuals approaching him—often weekly—saying they believed they might have Jewish roots. Often these were younger adults, who learned about this only after the death of a grandparent who apparently had hid this certain piece of “identify information”. Apparently “being Jewish” was not something one wanted to draw attention to after the Shoah, through communism and into modern Poland, with all its different dimensions. I wonder- and today? What about today?

Krakow is different than most of what I saw and experienced in Poland as so much of its “Jewishness” is not only about absence but a certain type of presence. The fact that Krakow was not destroyed during WW II means that you can still see seven well-preserved synagogues standing, the Jewish Quarter has restaurants with Hebrew or Yiddish signs. If you know where to look and do it diligently, you can still find some original Yiddish writing on some walls, there are memorial signs here and there about Jewish families of the past, and of course, Jewish tragedies. This captivated me.

Our free walking tour about the Jews of Krakow during the Holocaust stands out in my mind as it took us through areas where original buildings still stand in what was the ghetto, where the horrors and the pain of the past have physical manifestation of memory. It was at the end of this tiring 2.5 tour on a hot Krakow afternoon that the tears of both Merav and I finally came forth at the Empty Chairs Memorial: 70 bronze chairs - each chair symbolizes approximately 1,000 Jewish individuals who were deported or killed from the Kraków Ghetto. It is located in Kraków’s Ghetto Heroes Square (Plac Bohaterów Getta) across from the last remnant of the Kraków Ghetto wall. The scattered chairs represent the loss of lives, the empty homes and public spaces left behind, and the disrupted families echoing through empty seats. Their irregular placement reflects the chaotic and abrupt nature of the deportations and the voids created in the community.

We were approached by a young woman participant in the group, a Hebrew-speaking French woman, a psychotherapist, who had lived in Israel for years and now resides in the US. She was by chance attending a conference in Krakow and thought to take the tour. She asked quietly out loud at the end of the tour if anyone wanted to stay an extra moment while she said a prayer in memory of the victims that were deported from this very area. The entire group dispersed as she, Merav and I stood alone reading the mourning prayer of “El Male Rachamim”- ‘He who is full of mercy”. It was here, on this infamously tragic spot, left alone as the group dispersed, amidst the randomly scattered bronze chairs, with the word of “mercy” being said aloud, that our “communal tears” finally came forward...

How “Jewish” is the Jewish Cultural Festival?

What an impressive event! Who could have imagined such a public place of singing, dancing, learning, eating and drinking in Krakow’s Jewish Quarter 30-40 years ago? Attendance varies each year but consistently remains in the 20–30,000 range, making it one of the world’s largest Jewish cultural festivals! The event comprises some 200+ events, funding comes from Polish public and governmental sources as well as international foundations and philanthropic funds, even the Israeli government pitches in a bit via the embassy in Poland.

The event was a brainchild of one yet another impressive non-Jewish Polish activist for Jewish culture, Janusz Makuch, nearly 40 years ago. Janusz first became interested in Jews and Jewish culture in the early 1980s, while he was a university student in Poland. His awakening began when he read the works of Isaac Bashevis Singer, the Nobel Prize–winning Yiddish writer. Singer’s stories opened for him a window into a rich, vanished world of Jewish life in Poland—one that had been almost entirely erased from public memory during the communist era.

Makuch has said in interviews that, at that time, Jewish culture was not spoken about openly in Polish society. There was silence, discomfort, or ignorance surrounding the Jewish presence that had existed for centuries. He described how this absence of memory stirred something in him—a desire to understand what had been lost and to bring it back into Polish consciousness. Since that time, Janusz is the ultimate “changemaker”, he has run the festival from its inception, he is the man with the dream, the sense of purpose, inspiration and ability to make things happen.

But...but...

What is exactly “Jewish” about all this, I find myself wondering, not only the festival but the whole thriving “Jewish Quarter”? Yes, there are 7 synagogues, but how many Jews actually pray in them? Aren’t we actually talking about museums that still use the word “synagogue”? “Jewish tourism” seems to thrive, one can see shops selling a “Jewish man with a beard” dolls, restaurants sell “Jewish food”- not sure what that is exactly as it also openly advertises that it serves pork. The great majority of the visitors as well as the participants are not Jewish, which is nice for cross-cultural exchange, but what does this mean for the authenticity of it all? Janusz usually brings in all kinds of artists from Israel and the US, so in any given festival we might have Israelis of Moroccan or Yemenite descent presenting “Jewish music” in Poland, as well as all kinds of non-Jews who play klezmer or other kinds of “ethnic music” for Polish tourists. It leaves one thinking about “Jewish Culture”.

I went to one of the activities in the festival billed as “Deep Listening in the Streets of Kazimierz, expecting an opportunity to have someone deeply listen to some of the many thoughts and feelings on my chest during this trip, but there was not a word or opportunity to really engage at all with the Holocaust history. I later realized that the Holocaust is not at all the focus here, it is “around” but not center stage at all. The festival wants to focus on revival and celebration of Jewish culture—music, food, spirituality—rather than the devastation of the Holocaust. I guess that’s a good idea, but...does this make sense? For example, festival attendees can enjoy Klezmer concerts and falafel stands in Kazimierz, often just meters from sites where Jews were deported or killed, without necessarily engaging with the horror that occurred there. I find myself going back and forth with this in my mind.

Good examples of this ambivalence is the Hevre and bar and cafe. Housed in a former synagogue- antique chandeliers, high ceilings, peeling fresco fragments, and a visible mechitza (separate women’s seating area), all blend into a place where people come for beer, winding and dining. Both Merav and I were thrown off by this- is this a good or bad thing? If nobody would make use of these old buildings then they would be torn down and renovated, isn’t this a good way to keep some human activity going, connecting the past and the future? I am sure that this very discussion has taken place time in again over the last few decades in Krakow as well as Poland in general.

Jewish culture or not Jewish culture, what is for sure is that tourism has found that one can combine “dark sites” with “have fun sites” and make a nice profit in doing so. And we too found that it was a lot of fun dancing to Polish big band music from the 1920’s and 30’s. Past and present have various ways to link up.

Giving Testimony where my father never did: at the Polin Museum

I have chosen to end this piece of writing with something that took place actually right towards the beginning of our Poland journey. My reason for doing so is that it feels to me more of a “closing” than an “opening”, even though my real feeling is that it all is just “ongoing”.

About a month before our departure for Poland, when the actual plans were just getting underway, a Servas friend of mine who works at the Polin Museum asked me if I would be willing and interested in “giving testimony” by video about my father’s experience as part their oral history program. I immediately agreed, feeling a surge of meaning and purpose in the very invitation! My father’s story in the Shoah has been so close to me for decades, peaking in the work I did in making his testimony into a short film I have called “A Sacred Legacy”, of 17 minutes, and then even shorter one of less than 10 minutes. I do not openly publish this video, for fear of defiling the personal exposure of my father and his legacy. I have shown it selectively, however, to whom I feel are appropriate individuals and audiences both online and in person. Ever since my father died in 2019 I have felt it my duty to share this whenever I could. I have learnt over time that this film is not only about my father’s tragic losses and experiences but it is for me a “formative story”, that in some very profound way defines my deep-seated values and perspectives on life. Even back in 2007 when I worked with a video editor on the entire 3.5 hour film of my father’s story, I knew that documenting even the smallest details were vital for me. I have always felt “responsible” for knowing, documenting and conveying this story, and this sense of responsibility has kept me up nights to make sure I was doing my best to “get it right”.

Josef and his photographic assistant sat me up in a chair in a small room turned the camera on and we were off…I warned Josef at the start that I knew very much about my father’s story and could go on “forever” on it, that it would be best to just stop me if I am giving too much information. I began to tell the story “from the beginning”, about Zhetl, about his family, feeling that Josef would soon get bored and stop me. But he didn’t. In fact, he never stopped me as I went through my father’s life, every so often saying- “Wait, I forgot an important story”… I was amazed and humbled by Josef’s patience always fearful to “overdo the invitation” to tell it all.

I felt very empowered to do this. For years I have deliberated and made what some might call “obsessive” efforts to gather every bit of information, document, photo, name of person, event that my father ever wrote or told about on his experiences. As I spoke to Josef in front of the camera I felt my father’s presence in me, I felt pride in being able to do this for him, for his beloved parents and siblings who were taken from him so brutally. If not I, then who? I felt that I was fulfilling a mission to tell this story to the unidentified people who would find this interview on the Polin website and press the link to watch. Time and again my inner dialogue was saying- “What is the importance of this? After all, there are thousands of stories out there, what is the difference of one more or one less.” And still I continue.

Suddenly I became conscious that I was no longer talking only about my father’s story but was asking myself in the presence of Josef and the camera: Why am I so attached to this story? Why me and not my brothers, why make all this effort to tell it- it is not like there is anyone asking for it, I am being driven by an internal drive that I don’t always understand. Am I hanging on to something I do not want to let go of, and if so, why? Should I let go? What benefit will that do?...

And then, after a very long time of not saying a word, I felt Josef beginning to talk: “So…why do you think it is that you are so connected to this story and to telling it to others?”

Suddenly and uncharacteristically, I stood in my tracks. A flow of energy sweeped up into my eyes and I began to cry. For a few moments I found that I could not speak, and when I did it was halting: “Because…I feel…that if my father survived…there must be a meaning to that…and if I am alive because he survived…there must be a meaning for that…I want to know the meaning of my life…I want to feel that I am living my life with meaning and purpose…”

I shared with Josef that at the end of my doctoral dissertation I quoted a Holocaust survivor who was 7 years old when his parents were murdered and he and his brother were placed in a monastery in the Ukraine. That little Jewish boy, known today as Dr. Leon Chameides, went on to become a leading physician in the US. He once said: “"If you are a survivor, at some point, you are going to have to ask yourself, 'why did I survive?' And that puts a sort of burden to accomplish something with your life because you've got to, number one, deserved to have survived and number two, live life for those who didn't. “

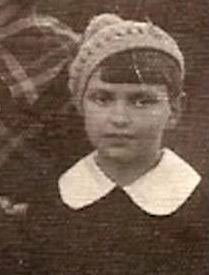

My father in an unforgettable moment on our family pilgrimage to Zhetl on August 6, 2000, the 58th memorial of the massacre of his town and family, cried out in the presence of my mother, myself and my two brothers, while clutching the monument of the mass grave: “Why did I survive!? What did I survive while the others went??...I was not better than them…God should have given me an answer…”

My father, August 6, 2000. Fifty eight years after the last massacre in Zhetl.

I know that this question that my father harbored in his heart to his last days on earth is not only his question. In some profound way, which I do not understand, this question has been passed on to me, for me to wrestle with to the best of my ability, in my own way. It is an existential question that may have no answer but nevertheless will stay with me. That I may be worthy to pass on the story and to live in accordance with its legacy.

To Sum Up- How was Poland?

When someone asks me, “How was your trip to Poland?”, even now, just three weeks since our return, I am really not sure how to answer. I think the best answer would be, “meaningful and complicated.” For me at this time, visiting Poland was full of paradoxes, contradictions, peak moments of transcendence as well as moments of disappointment. Be that as it may, I feel that the impact of my experience in Poland is still ongoing within me. I believe it will be that way for some time. I really did get more than I bargained for…

Comments